Prelude

This is the third post in a three part series that will provide an understanding of the mechanics and semantics behind the scheduler in Go. This post focuses on concurrency.

Index of the three part series:

- Scheduling In Go : Part I - OS Scheduler

- Scheduling In Go : Part II - Go Scheduler

- Scheduling In Go : Part III - Concurrency

Introduction

When I’m solving a problem, especially if it’s a new problem, I don’t initially think about whether concurrency is a good fit or not. I look for a sequential solution first and make sure that it’s working. Then after readability and technical reviews, I will begin to ask the question if concurrency is reasonable and practical. Sometimes it’s obvious that concurrency is a good fit and other times it’s not so clear.

In the first part of this series, I explained the mechanics and semantics of the OS scheduler that I believe are important if you plan on writing multithreaded code. In the second part, I explained the semantics of the Go scheduler that I believe are important for understanding how to write concurrent code in Go. In this post, I will begin to bring the mechanics and semantics of the OS and Go schedulers together to provide a deeper understanding on what concurrency is and isn’t.

The goals of this post are:

Provide guidance on the semantics you must consider to determine if a workload is suitable for using concurrency.

Show you how different types of workloads change the semantics and therefore the engineering decisions you will want to make.

What is Concurrency

Concurrency means “out of order” execution. Taking a set of instructions that would otherwise be executed in sequence and finding a way to execute them out of order and still produce the same result. For the problem in front of you, it has to be obvious that out of order execution would add value. When I say value, I mean add enough of a performance gain for the complexity cost. Depending on your problem, out of order execution may not be possible or even make sense.

It’s also important to understand that concurrency is not the same as parallelism. Parallelism means executing two or more instructions at the same time. This is a different concept from concurrency. Parallelism is only possible when you have at least 2 operating system (OS) and hardware threads available to you and you have at least 2 Goroutines, each executing instructions independently on each OS/hardware thread.

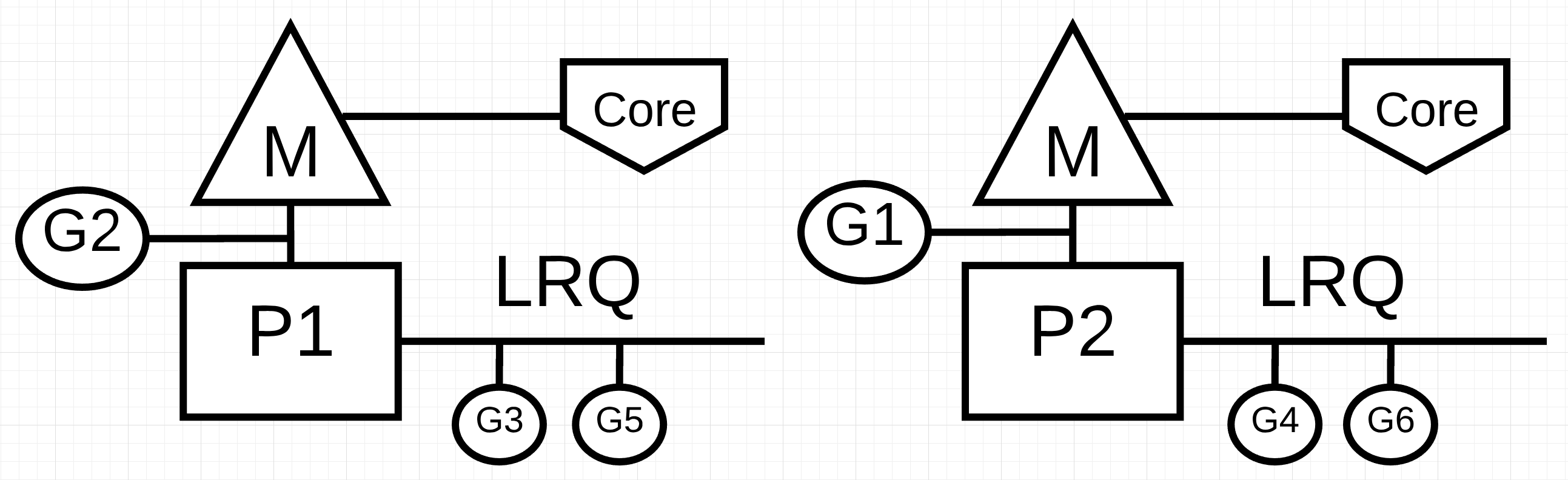

Figure 1 : Concurrency vs Parallelism

In figure 1, you see a diagram of two logical processors (P) each with their independent OS thread (M) attached to an independent hardware thread (Core) on the machine. You can see two Goroutines (G1 and G2) are executing in parallel, executing their instructions on their respective OS/hardware thread at the same time. Within each logical processor, three Goroutines are taking turns sharing their respective OS thread. All these Goroutines are running concurrently, executing their instructions in no particular order and sharing time on the OS thread.

Here’s the rub, sometimes leveraging concurrency without parallelism can actually slow down your throughput. What’s also interesting is, sometimes leveraging concurrency with parallelism doesn’t give you a bigger performance gain than you might otherwise think you can achieve.

Workloads

How do you know when out of order execution may be possible or make sense? Understanding the type of workload your problem is handling is a great place to start. There are two types of workloads that are important to understand when thinking about concurrency.

CPU-Bound: This is a workload that never creates a situation where Goroutines naturally move in and out of waiting states. This is work that is constantly making calculations. A Thread calculating Pi to the Nth digit would be CPU-Bound.

IO-Bound: This is a workload that causes Goroutines to naturally enter into waiting states. This is work that consists in requesting access to a resource over the network, or making system calls into the operating system, or waiting for an event to occur. A Goroutine that needs to read a file would be IO-Bound. I would include synchronization events (mutexes, atomic), that cause the Goroutine to wait as part of this category.

With CPU-Bound workloads you need parallelism to leverage concurrency. A single OS/hardware thread handling multiple Goroutines is not efficient since the Goroutines are not moving in and out of waiting states as part of their workload. Having more Goroutines than there are OS/hardware threads can slow down workload execution because of the latency cost (the time it takes) of moving Goroutines on and off the OS thread. The context switch is creating a “Stop The World” event for your workload since none of your workload is being executed during the switch when it otherwise could be.

With IO-Bound workloads you don’t need parallelism to use concurrency. A single OS/hardware thread can handle multiple Goroutines with efficiency since the Goroutines are naturally moving in and out of waiting states as part of their workload. Having more Goroutines than there are OS/hardware threads can speed up workload execution because the latency cost of moving Goroutines on and off the OS thread is not creating a “Stop The World” event. Your workload is naturally stopped and this allows a different Goroutine to leverage the same OS/hardware thread efficiently instead of letting the OS/hardware thread sit idle.

How do you know how many Goroutines per hardware thread provides the best throughput? Too few Goroutines and you have more idle time. Too many Goroutines and you have more context switch latency time. This is something for you to think about but beyond the scope of this particular post.

For now it’s important to review some code to solidify your ability to identify when a workload can leverage concurrency, when it can’t and if parallelism is needed or not.

Adding Numbers

We don’t need complex code to visualize and understand these semantics. Look at the following function named add that sums a collection of integers.

Listing 1

https://play.golang.org/p/r9LdqUsEzEz

36 func add(numbers []int) int {

37 var v int

38 for _, n := range numbers {

39 v += n

40 }

41 return v

42 }

In listing 1 on line 36, a function named add is declared that takes a collection of integers and returns the sum of the collection. It starts on line 37 with the declaration of the v variable to contain the sum. Then on line 38, the function traverses the collection linearly and each number is added to the current sum on line 39. Finally on line 41, the function returns the final sum back to the caller.

Question: is the add function a workload that is suitable for out of order execution? I believe the answer is yes. The collection of integers could be broken up into smaller lists and those lists could be processed concurrently. Once all the smaller lists are summed, the set of sums could be added together to produce the same answer as the sequential version.

However, there is another question that comes to mind. How many smaller lists should be created and processed independently to get the best throughput? To answer this question you must know what kind of workload add is performing. The add function is performing a CPU-Bound workload because the algorithm is performing pure math and nothing it does would cause the goroutine to enter into a natural waiting state. This means using one Goroutine per OS/hardware thread is all that is needed for good throughput.

Listing 2 below is my concurrent version of add.

Note: There are several ways and options you can take when writing a concurrent version of add. Don’t get hung up on my particular implementation at this time. If you have a more readable version that performs the same or better I would love for you to share it.

Listing 2

https://play.golang.org/p/r9LdqUsEzEz

44 func addConcurrent(goroutines int, numbers []int) int {

45 var v int64

46 totalNumbers := len(numbers)

47 lastGoroutine := goroutines - 1

48 stride := totalNumbers / goroutines

49

50 var wg sync.WaitGroup

51 wg.Add(goroutines)

52

53 for g := 0; g < goroutines; g++ {

54 go func(g int) {

55 start := g * stride

56 end := start + stride

57 if g == lastGoroutine {

58 end = totalNumbers

59 }

60

61 var lv int

62 for _, n := range numbers[start:end] {

63 lv += n

64 }

65

66 atomic.AddInt64(&v, int64(lv))

67 wg.Done()

68 }(g)

69 }

70

71 wg.Wait()

72

73 return int(v)

74 }

In Listing 2, the addConcurrent function is presented which is the concurrent version of the add function. The concurrent version uses 26 lines of code as opposed to the 5 lines of code for the non-concurrent version. There is a lot of code so I will only highlight the important lines to understand.

Line 48: Each Goroutine will get their own unique but smaller list of numbers to add. The size of the list is calculated by taking the size of the collection and dividing it by the number of Goroutines.

Line 53: The pool of Goroutines are created to perform the adding work.

Line 57-59: The last Goroutine will add the remaining list of numbers which may be greater than the other Goroutines.

Line 66: The sum of the smaller lists are summed together into a final sum.

The concurrent version is definitely more complex than the sequential version but is the complexity worth it? The best way to answer that question is to create a benchmark. For these benchmarks I have used a collection of 10 million numbers with the garbage collector turned off. There is a sequential version that uses the add function and a concurrent version that uses the addConcurrent function.

Listing 3

func BenchmarkSequential(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

add(numbers)

}

}

func BenchmarkConcurrent(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

addConcurrent(runtime.NumCPU(), numbers)

}

}

Listing 3 shows the benchmark functions. Here are the results when only a single OS/hardware thread is available for all Goroutines. The sequential version is using 1 Goroutine and the concurrent version is using runtime.NumCPU or 8 Goroutines on my machine. In this case, the concurrent version is leveraging concurrency without parallelism.

Listing 4

10 Million Numbers using 8 goroutines with 1 core

2.9 GHz Intel 4 Core i7

Concurrency WITHOUT Parallelism

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

$ GOGC=off go test -cpu 1 -run none -bench . -benchtime 3s

goos: darwin

goarch: amd64

pkg: github.com/ardanlabs/gotraining/topics/go/testing/benchmarks/cpu-bound

BenchmarkSequential 1000 5720764 ns/op : ~10% Faster

BenchmarkConcurrent 1000 6387344 ns/op

BenchmarkSequentialAgain 1000 5614666 ns/op : ~13% Faster

BenchmarkConcurrentAgain 1000 6482612 ns/op

Note: Running a benchmark on your local machine is complicated. There are so many factors that can cause your benchmarks to be inaccurate. Make sure your machine is as idle as possible and run benchmarks a few times. You want to make sure you see consistency in the results. Having the benchmark run twice by the testing tool is giving this benchmark the most consistent results.

The benchmark in listing 4 shows that the Sequential version is approximately 10 to 13 percent faster than the Concurrent when only a single OS/hardware thread is available for all Goroutines. This is what I would have expected since the concurrent version has the overhead of context switches on that single OS thread and the management of the Goroutines.

Here are the results when an individual OS/hardware thread is available for each Goroutine. The sequential version is using 1 Goroutine and the concurrent version is using runtime.NumCPU or 8 Goroutines on my machine. In this case, the concurrent version is leveraging concurrency with parallelism.

Listing 5

10 Million Numbers using 8 goroutines with 8 cores

2.9 GHz Intel 4 Core i7

Concurrency WITH Parallelism

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

$ GOGC=off go test -cpu 8 -run none -bench . -benchtime 3s

goos: darwin

goarch: amd64

pkg: github.com/ardanlabs/gotraining/topics/go/testing/benchmarks/cpu-bound

BenchmarkSequential-8 1000 5910799 ns/op

BenchmarkConcurrent-8 2000 3362643 ns/op : ~43% Faster

BenchmarkSequentialAgain-8 1000 5933444 ns/op

BenchmarkConcurrentAgain-8 2000 3477253 ns/op : ~41% Faster

The benchmark in listing 5 shows that the concurrent version is approximately 41 to 43 percent faster than the sequential version when an individual OS/hardware thread is available for each Goroutine. This is what I would have expected since all the Goroutines are now running in parallel, eight Goroutines executing their concurrent work at the same time.

Sorting

It’s important to understand that not all CPU-bound workloads are suitable for concurrency. This is primarily true when it’s very expensive to either break work up, and/or combine all the results. An example of this can be seen with the sorting algorithm called Bubble sort. Look at the following code that implements Bubble sort in Go.

Listing 6

https://play.golang.org/p/S0Us1wYBqG6

01 package main

02

03 import "fmt"

04

05 func bubbleSort(numbers []int) {

06 n := len(numbers)

07 for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

08 if !sweep(numbers, i) {

09 return

10 }

11 }

12 }

13

14 func sweep(numbers []int, currentPass int) bool {

15 var idx int

16 idxNext := idx + 1

17 n := len(numbers)

18 var swap bool

19

20 for idxNext < (n - currentPass) {

21 a := numbers[idx]

22 b := numbers[idxNext]

23 if a > b {

24 numbers[idx] = b

25 numbers[idxNext] = a

26 swap = true

27 }

28 idx++

29 idxNext = idx + 1

30 }

31 return swap

32 }

33

34 func main() {

35 org := []int{1, 3, 2, 4, 8, 6, 7, 2, 3, 0}

36 fmt.Println(org)

37

38 bubbleSort(org)

39 fmt.Println(org)

40 }

In listing 6, there is an example of Bubble sort written in Go. This sorting algorithm sweeps through a collection of integers swapping values on every pass. Depending on the ordering of the list, it may require multiple passes through the collection before everything is sorted.

Question: is the bubbleSort function a workload that is suitable for out of order execution? I believe the answer is no. The collection of integers could be broken up into smaller lists and those lists could be sorted concurrently. However, after all the concurrent work is done there is no efficient way to sort the smaller lists together. Here is an example of a concurrent version of Bubble sort.

Listing 8

01 func bubbleSortConcurrent(goroutines int, numbers []int) {

02 totalNumbers := len(numbers)

03 lastGoroutine := goroutines - 1

04 stride := totalNumbers / goroutines

05

06 var wg sync.WaitGroup

07 wg.Add(goroutines)

08

09 for g := 0; g < goroutines; g++ {

10 go func(g int) {

11 start := g * stride

12 end := start + stride

13 if g == lastGoroutine {

14 end = totalNumbers

15 }

16

17 bubbleSort(numbers[start:end])

18 wg.Done()

19 }(g)

20 }

21

22 wg.Wait()

23

24 // Ugh, we have to sort the entire list again.

25 bubbleSort(numbers)

26 }

In Listing 8, the bubbleSortConcurrent function is presented which is a concurrent version of the bubbleSort function. It uses multiple Goroutines to sort portions of the list concurrently. However, what you are left with is a list of sorted values in chunks. Given a list of 36 numbers, split in groups of 12, this would be the resulting list if the entire list is not sorted once more on line 25.

Listing 9

Before:

25 51 15 57 87 10 10 85 90 32 98 53

91 82 84 97 67 37 71 94 26 2 81 79

66 70 93 86 19 81 52 75 85 10 87 49

After:

10 10 15 25 32 51 53 57 85 87 90 98

2 26 37 67 71 79 81 82 84 91 94 97

10 19 49 52 66 70 75 81 85 86 87 93

Since the nature of Bubble sort is to sweep through the list, the call to bubbleSort on line 25 will negate any potential gains from using concurrency. With Bubble sort, there is no performance gain by using concurrency.

Reading Files

Two CPU-Bound workloads have been presented, but what about an IO-Bound workload? Are the semantics different when Goroutines are naturally moving in and out of waiting states? Look at an IO-Bound workload that reads files and performs a text search.

This first version is a sequential version of a function called find.

Listing 10

https://play.golang.org/p/8gFe5F8zweN

42 func find(topic string, docs []string) int {

43 var found int

44 for _, doc := range docs {

45 items, err := read(doc)

46 if err != nil {

47 continue

48 }

49 for _, item := range items {

50 if strings.Contains(item.Description, topic) {

51 found++

52 }

53 }

54 }

55 return found

56 }

In listing 10, you see the sequential version of the find function. On line 43, a variable named found is declared to maintain a count for the number of times the specified topic is found inside a given document. Then on line 44, the documents are iterated over and each document is read on line 45 using the read function. Finally on line 49-53, the Contains function from the strings package is used to check if the topic can be found inside the collection of items read from the document. If the topic is found, the found variable is incremented by one.

Here is the implementation of the read function that is being called by find.

Listing 11

https://play.golang.org/p/8gFe5F8zweN

33 func read(doc string) ([]item, error) {

34 time.Sleep(time.Millisecond) // Simulate blocking disk read.

35 var d document

36 if err := xml.Unmarshal([]byte(file), &d); err != nil {

37 return nil, err

38 }

39 return d.Channel.Items, nil

40 }

The read function in listing 11 starts with a time.Sleep call for one millisecond. This call is being used to mock the latency that could be produced if we performed an actual system call to read the document from disk. The consistency of this latency is important for accurately measuring the performance of the sequential version of find against the concurrent version. Then on lines 35-39, the mock xml document stored in the global variable file is unmarshaled into a struct value for processing. Finally, a collection of items is returned back to the caller on line 39.

With the sequential version in place, here is the concurrent version.

Note: There are several ways and options you can take when writing a concurrent version of find. Don’t get hung up on my particular implementation at this time. If you have a more readable version that performs the same or better I would love for you to share it.

Listing 12

https://play.golang.org/p/8gFe5F8zweN

58 func findConcurrent(goroutines int, topic string, docs []string) int {

59 var found int64

60

61 ch := make(chan string, len(docs))

62 for _, doc := range docs {

63 ch <- doc

64 }

65 close(ch)

66

67 var wg sync.WaitGroup

68 wg.Add(goroutines)

69

70 for g := 0; g < goroutines; g++ {

71 go func() {

72 var lFound int64

73 for doc := range ch {

74 items, err := read(doc)

75 if err != nil {

76 continue

77 }

78 for _, item := range items {

79 if strings.Contains(item.Description, topic) {

80 lFound++

81 }

82 }

83 }

84 atomic.AddInt64(&found, lFound)

85 wg.Done()

86 }()

87 }

88

89 wg.Wait()

90

91 return int(found)

92 }

In Listing 12, the findConcurrent function is presented which is the concurrent version of the find function. The concurrent version uses 30 lines of code as opposed to the 13 lines of code for the non-concurrent version. My goal in implementing the concurrent version was to control the number of Goroutines that are used to process the unknown number of documents. A pooling pattern where a channel is used to feed the pool of Goroutines was my choice.

There is a lot of code so I will only highlight the important lines to understand.

Lines 61-64: A channel is created and populated with all the documents to process.

Line 65: The channel is closed so the pool of Goroutines naturally terminate when all the documents are processed.

Line 70: The pool of Goroutines is created.

Line 73-83: Each Goroutine in the pool receives a document from the channel, reads the document into memory and checks the contents for the topic. When there is a match, the local found variable is incremented.

Line 84: The sum of the individual Goroutine counts are summed together into a final count.

The concurrent version is definitely more complex than the sequential version but is the complexity worth it? The best way to answer this question again is to create a benchmark. For these benchmarks I have used a collection of 1 thousand documents with the garbage collector turned off. There is a sequential version that uses the find function and a concurrent version that uses the findConcurrent function.

Listing 13

func BenchmarkSequential(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

find("test", docs)

}

}

func BenchmarkConcurrent(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

findConcurrent(runtime.NumCPU(), "test", docs)

}

}

Listing 13 shows the benchmark functions. Here are the results when only a single OS/hardware thread is available for all Goroutines. The sequential is using 1 Goroutine and the concurrent version is using runtime.NumCPU or 8 Goroutines on my machine. In this case, the concurrent version is leveraging concurrency without parallelism.

Listing 14

10 Thousand Documents using 8 goroutines with 1 core

2.9 GHz Intel 4 Core i7

Concurrency WITHOUT Parallelism

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

$ GOGC=off go test -cpu 1 -run none -bench . -benchtime 3s

goos: darwin

goarch: amd64

pkg: github.com/ardanlabs/gotraining/topics/go/testing/benchmarks/io-bound

BenchmarkSequential 3 1483458120 ns/op

BenchmarkConcurrent 20 188941855 ns/op : ~87% Faster

BenchmarkSequentialAgain 2 1502682536 ns/op

BenchmarkConcurrentAgain 20 184037843 ns/op : ~88% Faster

The benchmark in listing 14 shows that the concurrent version is approximately 87 to 88 percent faster than the sequential version when only a single OS/hardware thread is available for all Goroutines. This is what I would have expected since all the Goroutines are efficiently sharing the single OS/hardware thread. The natural context switch happening for each Goroutine on the read call is allowing more work to get done over time on the single OS/hardware thread.

Here is the benchmark when using concurrency with parallelism.

Listing 15

10 Thousand Documents using 8 goroutines with 1 core

2.9 GHz Intel 4 Core i7

Concurrency WITH Parallelism

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

$ GOGC=off go test -run none -bench . -benchtime 3s

goos: darwin

goarch: amd64

pkg: github.com/ardanlabs/gotraining/topics/go/testing/benchmarks/io-bound

BenchmarkSequential-8 3 1490947198 ns/op

BenchmarkConcurrent-8 20 187382200 ns/op : ~88% Faster

BenchmarkSequentialAgain-8 3 1416126029 ns/op

BenchmarkConcurrentAgain-8 20 185965460 ns/op : ~87% Faster

The benchmark in listing 15 shows that bringing in the extra OS/hardware threads don’t provide any better performance.

Conclusion

The goal of this post was to provide guidance on the semantics you must consider to determine if a workload is suitable for using concurrency. I tried to provide examples of different types of algorithms and workloads so you could see the differences in semantics and the different engineering decisions that needed to be considered.

You can clearly see that with IO-Bound workloads parallelism was not needed to get a big bump in performance. Which is the opposite of what you saw with the CPU-Bound work. When it comes to an algorithm like Bubble sort, the use of concurrency would add complexity without any real benefit of performance. It’s important to determine if your workload is suitable for concurrency and then identify the type of workload you have to use the right semantics.