Prelude

This is the second post in a four part series that will provide an understanding of the mechanics and design behind pointers, stacks, heaps, escape analysis and value/pointer semantics in Go. This post focuses on heaps and escape analysis.

Index of the four part series:

- Language Mechanics On Stacks And Pointers

- Language Mechanics On Escape Analysis

- Language Mechanics On Memory Profiling

- Design Philosophy On Data And Semantics

Introduction

In the first post in this four part series, I taught the basics of pointer mechanics by using an example in which a value was shared down a goroutine’s stack. What I did not show you is what happens when you share a value up the stack. To understand this, you need to learn about another area of memory where values can live: the “heap”. With that knowledge, you can then begin to learn about “escape analysis”.

Escape analysis is the process that the compiler uses to determine the placement of values that are created by your program. Specifically, the compiler performs static code analysis to determine if a value can be placed on the stack frame for the function constructing it, or if the value must “escape” to the heap. In Go, there is no keyword or function you can use to direct the compiler in this decision. It’s only through the convention of how you write your code that dictates this decision.

Heaps

The heap is a second area of memory, in addition to the stack, used for storing values. The heap is not self cleaning like stacks, so there is a bigger cost to using this memory. Primarily, the costs are associated with the garbage collector (GC), which must get involved to keep this area clean. When the GC runs, it will use 25% of your available CPU capacity. Plus, it can potentially create microseconds of “stop the world” latency. The benefit of having the GC is that you don’t need to worry about managing heap memory, which historically has been complicated and error prone.

Values on the heap constitute memory allocations in Go. These allocations put pressure on the GC because every value on the heap that is no longer referenced by a pointer, needs to be removed. The more values that need to be checked and removed, the more work the GC must perform on every run. So, the pacing algorithm is constantly working to balance the size of the heap with the pace it runs at.

Sharing Stacks

In Go, no goroutine is allowed to have a pointer that points to memory on another goroutine’s stack. This is because the stack memory for a goroutine can be replaced with a new block of memory when the stack has to grow or shrink. If the runtime had to track pointers to other goroutine stacks, it would be too much to manage and the “stop the world” latency in updating pointers on those stacks would be overwhelming.

Here is an example of a stack that is replaced several times because of growth. Look at the output for lines 2 and 6. You will see the address of the string value inside the stack frame of main changes twice.

https://play.golang.org/p/pxn5u4EBSI

Escape Mechanics

Anytime a value is shared outside the scope of a function’s stack frame, it will be placed (or allocated) on the heap. It’s the job of the escape analysis algorithms to find these situations and maintain a level of integrity in the program. The integrity is in making sure that access to any value is always accurate, consistent and efficient.

Look at this example to learn the basic mechanics behind escape analysis.

https://play.golang.org/p/Y_VZxYteKO

Listing 1

01 package main

02

03 type user struct {

04 name string

05 email string

06 }

07

08 func main() {

09 u1 := createUserV1()

10 u2 := createUserV2()

11

12 println("u1", &u1, "u2", &u2)

13 }

14

15 //go:noinline

16 func createUserV1() user {

17 u := user{

18 name: "Bill",

19 email: "bill@ardanlabs.com",

20 }

21

22 println("V1", &u)

23 return u

24 }

25

26 //go:noinline

27 func createUserV2() *user {

28 u := user{

29 name: "Bill",

30 email: "bill@ardanlabs.com",

31 }

32

33 println("V2", &u)

34 return &u

35 }

I am using the go:noinline directive to prevent the compiler from inlining the code for these functions directly in main. Inlining would erase the function calls and complicate this example. I will introduce the side effects of inlining in the next post.

In Listing 1, you see a program with two different functions that create a user value and return the value back to the caller. Version 1 of the function is using value semantics on the return.

Listing 2

16 func createUserV1() user {

17 u := user{

18 name: "Bill",

19 email: "bill@ardanlabs.com",

20 }

21

22 println("V1", &u)

23 return u

24 }

I said the function is using value semantics on the return because the user value created by this function is being copied and passed up the call stack. This means the calling function is receiving a copy of the value itself.

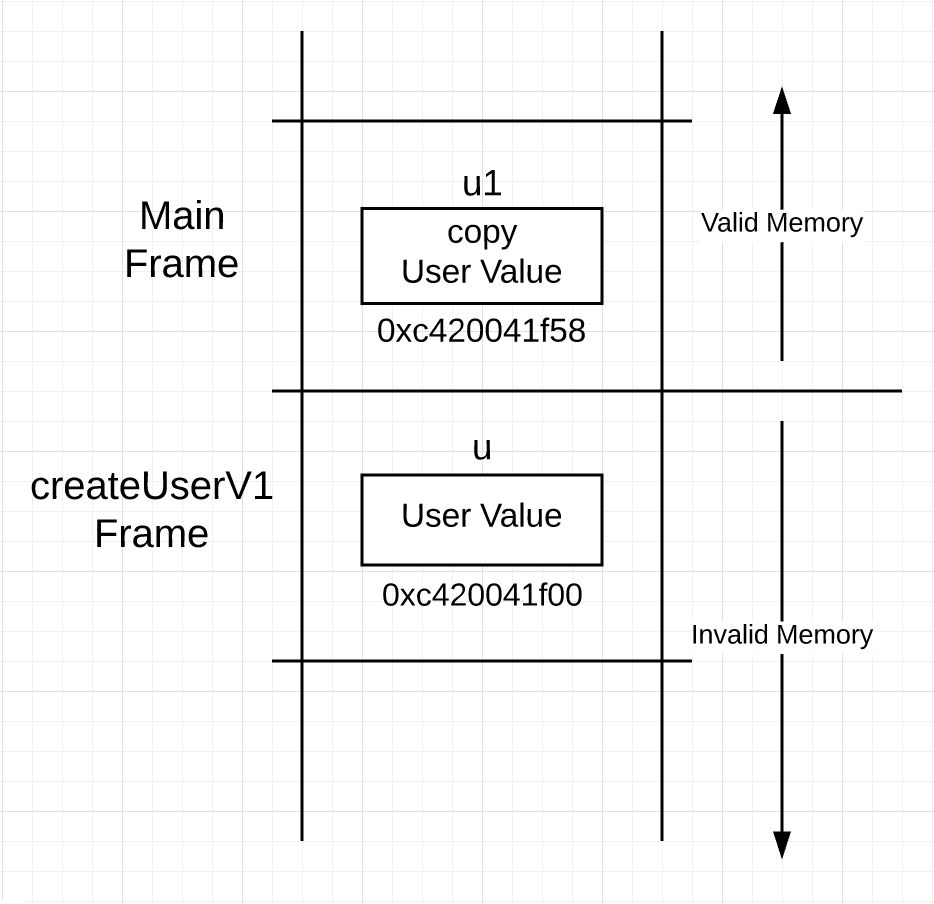

You can see the construction of a user value being performed on lines 17 through 20. Then on line 23, a copy of the user value is passed up the call stack and back to the caller. After the function returns, the stack looks like this.

Figure 1

You can see in Figure 1, a user value exists in both frames after the call to createUserV1. In Version 2 of the function, pointer semantics are being used on the return.

Listing 3

27 func createUserV2() *user {

28 u := user{

29 name: "Bill",

30 email: "bill@ardanlabs.com",

31 }

32

33 println("V2", &u)

34 return &u

35 }

I said the function is using pointer semantics on the return because the user value created by this function is being shared up the call stack. This means the calling function is receiving a copy of the address for the value.

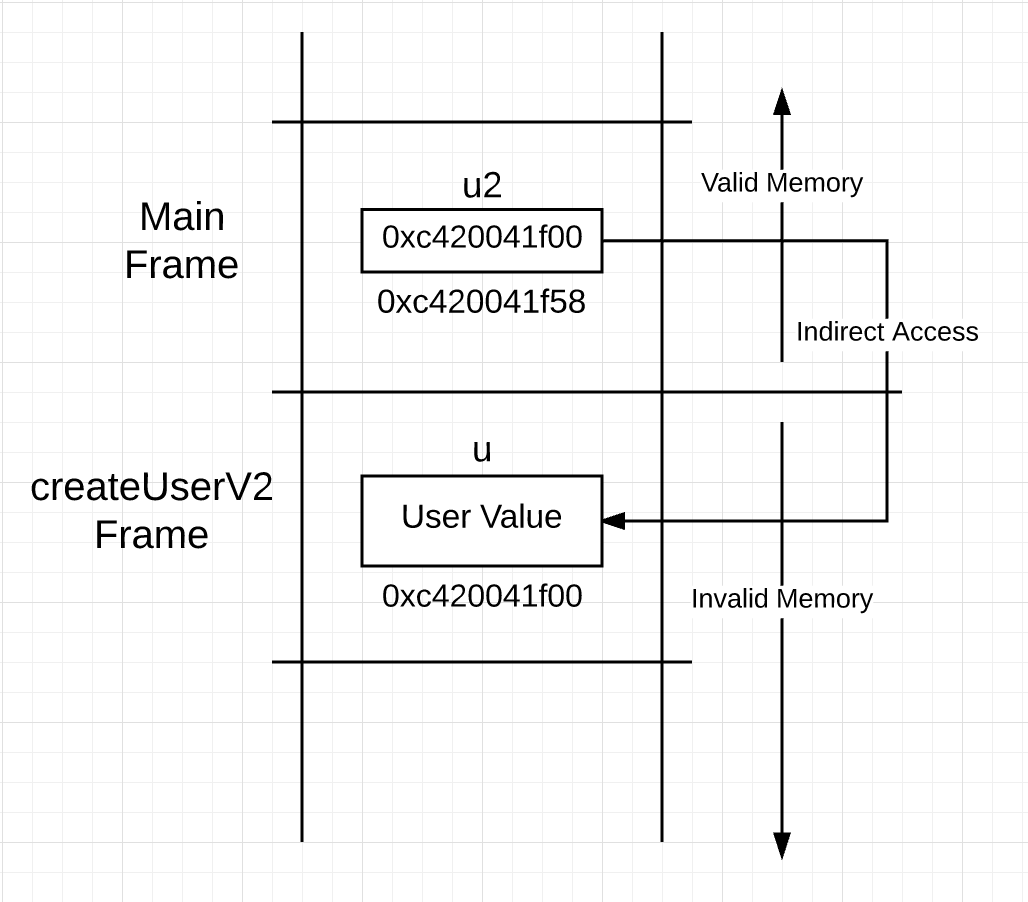

You can see the same struct literal being used on lines 28 through 31 to construct a user value, but on line 34 the return is different. Instead of passing a copy of the user value back up the call stack, a copy of the address for the user value is passed up. Based on this, you might think that the stack looks like this after the call.

Figure 2

If what you see in Figure 2 was really happening, you would have an integrity issue. The pointer is pointing down the call stack into memory that is no longer valid. On the next function call by main, that memory being pointed to is going to be re-framed and re-initialized.

This is where escape analysis begins to maintain integrity. In this case, the compiler will determine it’s not safe to construct the user value inside the stack frame of createUserV2, so instead it will construct the value on the heap. This will happen immediately during construction on line 28.

Readability

As you learned in the last post, a function has direct access to the memory inside its frame, through the frame pointer, but access to memory outside its frame requires indirect access. This means access to values that escape to the heap must be done indirectly through a pointer as well.

Remember what the code looks like for createUserV2.

Listing 4

27 func createUserV2() *user {

28 u := user{

29 name: "Bill",

30 email: "bill@ardanlabs.com",

31 }

32

33 println("V2", &u)

34 return &u

35 }

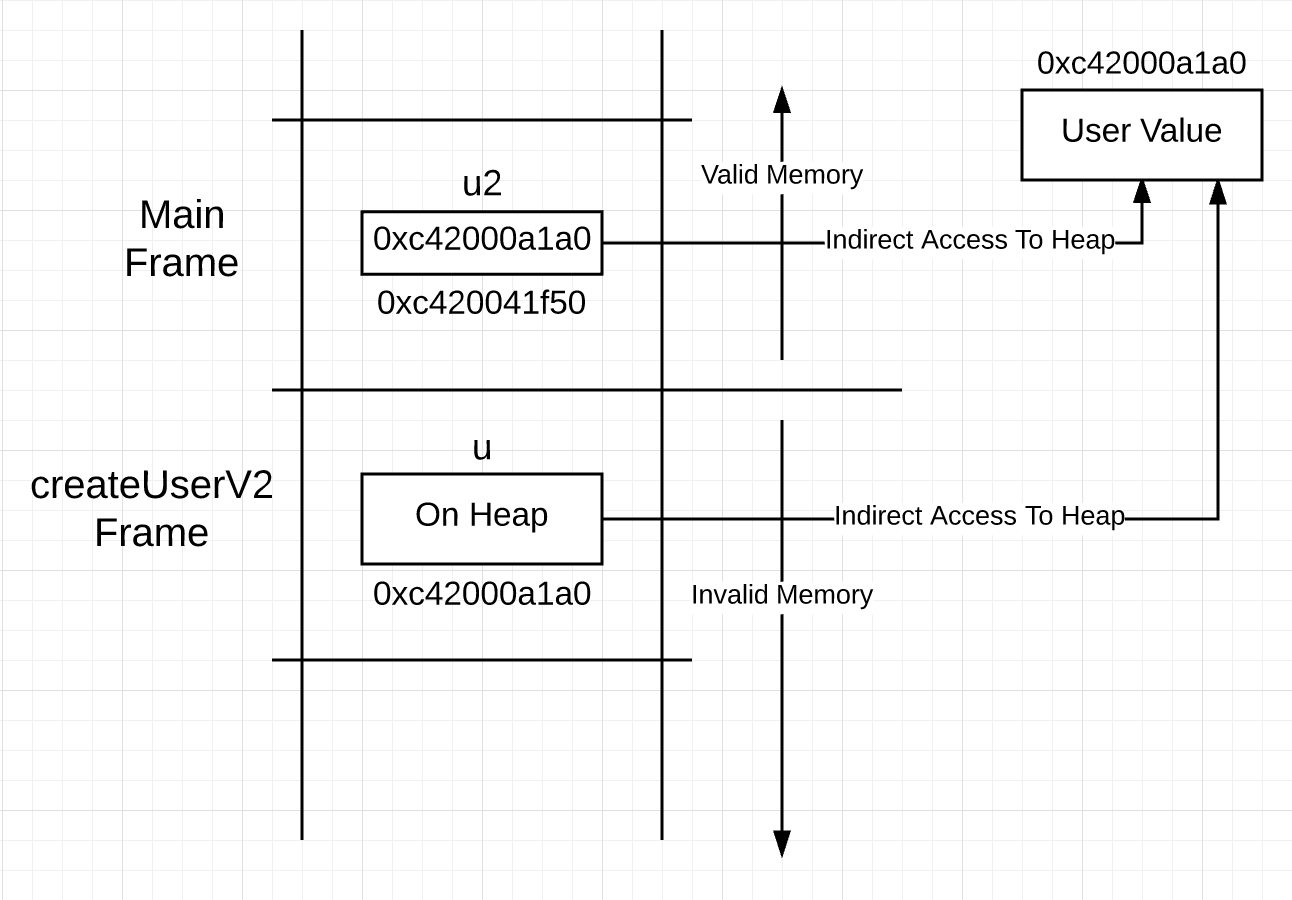

The syntax is hiding what is really happening in this code. The variable u declared on line 28 represents a value of type user. Construction in Go doesn’t tell you where a value lives in memory, so it’s not until the return statement on line 34, do you know the value will need to escape. This means, even though u represents a value of type user, access to this user value must be happening through a pointer underneath the covers.

You could visualize the stack looking like this after the function call.

Figure 3

The u variable on the stack frame for createUserV2, represents a value that is on the heap, not the stack. This means using u to access the value, requires pointer access and not the direct access the syntax is suggesting. You might think, why not make u a pointer then, since access to the value it represents requires the use of a pointer anyway?

Listing 5

27 func createUserV2() *user {

28 u := &user{

29 name: "Bill",

30 email: "bill@ardanlabs.com",

31 }

32

33 println("V2", u)

34 return u

35 }

If you do this, you are walking away from an important readability gain you can have in your code. Step away from the entire function for a second and just focus on the return.

Listing 6

34 return u

35 }

What does this return tell you? All that it says is that a copy of u is being passed up the call stack. However, what does the return tell you when you use the & operator?

Listing 7

34 return &u

35 }

Thanks to the & operator, the return now tells you that u is being shared up the call stack and therefore escaping to the heap. Remember, pointers are for sharing and replace the & operator for the word “sharing” as you read code. This is very powerful in terms of readability, something you don’t want to lose.

Here is another example where constructing values using pointer semantics hurts readability.

Listing 8

01 var u *user

02 err := json.Unmarshal([]byte(r), &u)

03 return u, err

You must share the pointer variable with the json.Unmarshal call on line 02 for this code to work. The json.Unmarshal call will create the user value and assign its address to the pointer variable. https://play.golang.org/p/koI8EjpeIx

What does this code say:

01 : Create a pointer of type user set to its zero value.

02 : Share u with the json.Unmarshal function.

03 : Return a copy of u with the caller.

It is not obviously clear that a user value, which was created by the json.Unmarshal function, is being shared with the caller.

How does readability change when using value semantics during construction?

Listing 9

01 var u user

02 err := json.Unmarshal([]byte(r), &u)

03 return &u, err

What does this code say:

01 : Create a value of type user set to its zero value.

02 : Share u with the json.Unmarshal function.

03 : Share u with the caller.

Everything is very clear. Line 02 is sharing the user value down the call stack into json.Unmarshal and line 03 is sharing the user value up the call stack back to the caller. This share will cause the user value to escape.

Use value semantics when constructing a value and leverage the readability of the & operator to make it clear how values are being shared.

Compiler Reporting

To see the decisions the compiler is making, you can ask the compiler to provide a report. All you need to do is use the -gcflags switch with the -m option on the go build call.

There are actually 4 levels of -m you can use, but beyond 2 levels the information is overwhelming. I will be using the 2 levels of -m.

Listing 10

$ go build -gcflags "-m -m"

./main.go:16: cannot inline createUserV1: marked go:noinline

./main.go:27: cannot inline createUserV2: marked go:noinline

./main.go:8: cannot inline main: non-leaf function

./main.go:22: createUserV1 &u does not escape

./main.go:34: &u escapes to heap

./main.go:34: from ~r0 (return) at ./main.go:34

./main.go:31: moved to heap: u

./main.go:33: createUserV2 &u does not escape

./main.go:12: main &u1 does not escape

./main.go:12: main &u2 does not escape

You can see the compiler is reporting the escape decisions. What is the compiler saying? First look at the createUserV1 and createUserV2 functions again for reference.

Listing 13

16 func createUserV1() user {

17 u := user{

18 name: "Bill",

19 email: "bill@ardanlabs.com",

20 }

21

22 println("V1", &u)

23 return u

24 }

27 func createUserV2() *user {

28 u := user{

29 name: "Bill",

30 email: "bill@ardanlabs.com",

31 }

32

33 println("V2", &u)

34 return &u

35 }

Start with this line in the report.

Listing 14

./main.go:22: createUserV1 &u does not escape

This is saying that the function call to println inside of the createUserV1 function is not causing the user value to escape to the heap. This must be checked because it is being shared with the println function.

Next look at these lines in the report.

Listing 15

./main.go:34: &u escapes to heap

./main.go:34: from ~r0 (return) at ./main.go:34

./main.go:31: moved to heap: u

./main.go:33: createUserV2 &u does not escape

These lines are saying, the user value associated with the u variable, which is of the named type user and assigned on line 31, is escaping because of the return on line 34. The last line is saying the same thing as before, the println call on line 33 is not causing the user value to escape.

Reading these reports can be confusing and can slightly change depending on whether the type of variable in question is based on a named or literal type.

Change u to be of the literal type *user instead of the named type user that it was before.

Listing 16

27 func createUserV2() *user {

28 u := &user{

29 name: "Bill",

30 email: "bill@ardanlabs.com",

31 }

32

33 println("V2", u)

34 return u

35 }

Run the report again.

Listing 17

./main.go:30: &user literal escapes to heap

./main.go:30: from u (assigned) at ./main.go:28

./main.go:30: from ~r0 (return) at ./main.go:34

Now the report is saying the user value referenced by the u variable, which is of the literal type *user and assigned on line 28, is escaping because of the return on line 34.

Conclusion

The construction of a value doesn’t determine where it lives. Only how a value is shared will determine what the compiler will do with that value. Anytime you share a value up the call stack, it is going to escape. There are other reasons for a value to escape which you will explore in the next post.

What these posts are trying to lead you to is guidelines for choosing value or pointer semantics for any given type. Each semantic comes with a benefit and cost. Value semantics keep values on the stack which reduces pressure on the GC. However, there are different copies of any given value that must be stored, tracked and maintained. Pointer semantics place values on the heap which can put pressure on the GC. However, they are efficient because there is only one value that needs to be stored, tracked and maintained. The key is using each semantic correctly, consistently and in balance.